Christianity without redemption?

What ‘woke religion’ reveals about secular morality (Part 2 of 3)

I concluded Part 1 of this essay by asking if woke is, in fact, not enough like a religion. So, in what way?

Traditional religion involves both a coherent view of the world and a workable modus vivendi, often forged over centuries of debate – and, yes, sometimes violent conflict – that leaves room for a certain amount of nuance. Agreement about the core principles of the faith allows for differences around the edges. Historically and today, fanaticism is the exception rather than the rule. Crucially, traditional religion involves some accommodation for human frailty: an acknowledgement that we all make mistakes, and usually some means to make amends or gain forgiveness.

It has often been said that woke is like Christianity without redemption. Rather than acknowledging that we are all sinners in need of forgiveness, activists tend to pounce on transgressions and anathematise the guilty. They insist on impossible (and ever-changing) standards, and indulge in purity spirals, driving adherents to ever-more extreme positions by reserving their harshest treatment for their own allies who fall short. And, once condemned, there is no way back. No wonder critics note with consternation that even the Puritans believed in redemption.

Describing woke as ‘Christianity without redemption’ is some qualification, however. Redemption is the whole point of Christianity. But Christian redemption, properly understood, is very different from forgiveness understood in secular, therapeutic terms – even if, in some important senses, Christianity continues to influence the way we think about forgiveness. The prevailing, post-Christian, pre-woke attitude to ‘sin’ is to acknowledge that we all make mistakes, but also to look for extenuating circumstances. ‘Judge not’ has been secularised, with ‘lest ye be judged’ left as a hypothetical that’s best not taken too seriously. We’d all be in trouble!

Indeed. And what’s often left out of the picture when it comes to redemption is what exactly we are redeemed from. Many contemporary Christians are embarrassed by the doctrine of Hell. But the idea of divine or cosmic punishment was not invented by Christian theologians; it exists in one form or another in just about all religions and cultural traditions. (I have explored the idea of Hell at leisure in my novel-after-Dante, Gehenna.)

In fact, disbelief in Hell may be something secular culture has contracted from embarrassed Christians rather than the other way round. Or, to put it slightly less mischievously, secular culture has inherited liberal Christians’ disbelief in the desirability of cosmic punishment. Or at least that’s been the prevailing consensus in secular culture until recently.

Redemption from what, then?

Tim Keller was the kind of Christian who believed without embarrassment in both Heaven and Hell. In an interview given in 2022, towards the end of his life, he noted that the wokeish younger generation now is far more justice-oriented than his own, more therapeutically-oriented Baby Boomer generation was. For that reason, he suggested hopefully that the idea of Hell as God’s judgement on evil is less offensive to those exploring Christianity than it was when he was young.

For many of the ‘woke is a religion’ crowd, this is just the kind of development they fear. Of all the retrograde ideas social justice activists could take from religion, surely the idea of damning sinners to Hell is the worst? Even if the woke don’t believe in an actual Hell, the idea that anyone ultimately deserves punishment rather than understanding and forgiveness is radically at odds with the post-Christian consensus we have lived with for generations. And surely not in a ‘progressive’ way!

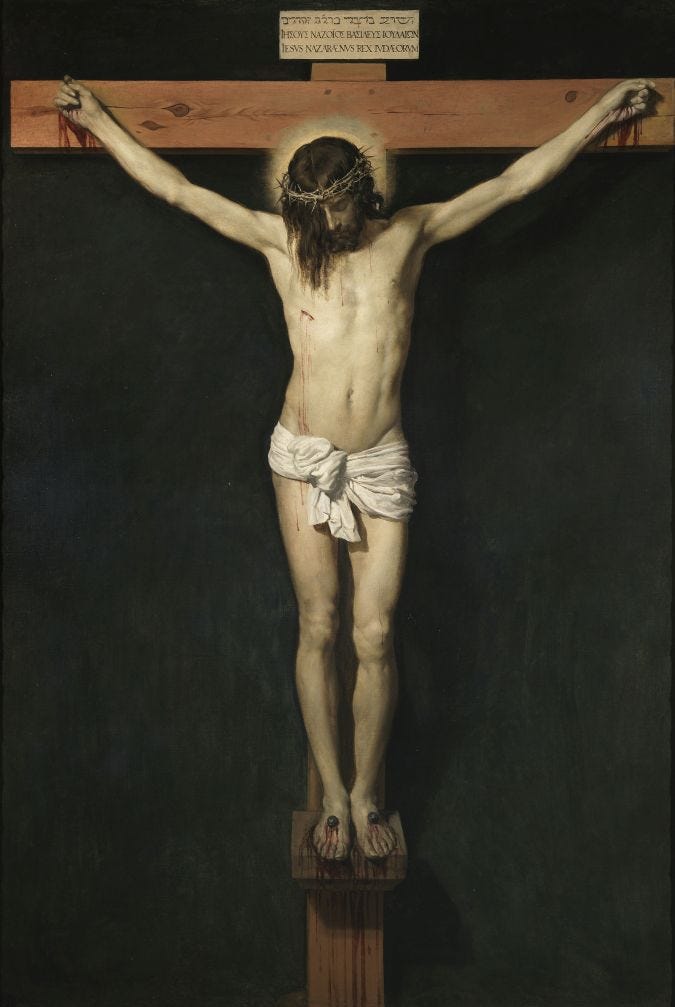

Certainly, the idea of damnation with no hope of redemption is a one-sided take on the Christian inheritance. But so too is the idea of redemption with no fear of damnation. While redemption implies something to be redeemed from, however, damnation does not necessarily imply the possibility of a way out. We could just be left to suffer our fate. So, after the question of what sinners are redeemed from in Christianity comes a second overlooked question: how exactly is this brought about? A clue to the answer can be found in centuries of Christian art. Jesus Christ is not depicted waving a magic wand.

Given that many Christians seem less than keen on it, it’s hardly surprising that non-Christians tend to be no more enamoured of the claim that Jesus had to die on the cross for their sins. If God loves us and wants to forgive us, many have asked, why didn’t he just do it? The question surely hinges on what we mean by forgiveness, and indeed justice. Or, in this case, what Christianity means by those things. So, with apologies to Baby Boomers and social justice warriors alike, let’s go back to the Bible.

When John the Baptist sends his disciples to ask Jesus if he is the messiah (Matthew 11), Jesus tells them, ‘Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up, and the poor have good news preached to them’. There is an obvious, ‘Marxist’ objection to this. Why is it that everyone has their disability or ailment (even death!) cancelled out, except the poor, who are fobbed off with ‘good news’? Why not ‘the poor are made well-off’?

Accounting for sin

It seems Jesus has something else in mind when he talks about poverty. In the sermon on the mount, too, he singles out ‘the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven’ (Matthew 5). Whether they are also poor materially or not, Jesus is more interested in their spiritual condition. And that’s where he brings ‘good news’. Just as when he tells a paralysed man that his sins are forgiven (Matthew 9), Jesus deals with the problem that concerns him, not necessarily the one that’s presented to him. He goes on to heal that man’s body only to demonstrate his authority to the watching scribes. If he can do that, then when he said the man’s sins were forgiven…

Here we are faced with a major clash of worldviews. When Jesus told the man his sins were forgiven, he was claiming to have effected something just as objective as healing his paralysis. The scribes understood this, which was why they said (to themselves) that he was blaspheming. Only God can forgive sin.

Today’s scribes have a different reaction. For us, forgiveness is not an objective thing at all, but the prerogative of a wronged party. If we say to ourselves, ‘Who does Jesus think he is?’ we are not objecting to his taking the part of God, but to God taking the part of the victim. In doing so, are we missing something?

I’ll try to unpack the significance of that question in the third and final part of this essay.

In Greek and I'm sure other ancient tragedies, the powerful driver of narrative is revenge. This in turn provides us with Christianity's progressive, and materially necessary to an emerging society, content: forgiveness. Forgiveness brings stability. Away with the antisocial pursuit of the person, and their family, and everyone they knew (to paraphrase Clint in The Unforgiven). So, my question, in abandoning forgiveness and resurrecting revenge, is Wokiness premodern?